They activate your sense of competitiveness, exploration, collaboration, or expression. Rather than passively sitting back, you must solve problems, overcome challenges, gain skills, and experience the highs and lows that come with that.

You are part of the story, rather than just a consumer of it. A good game makes you believe you are that person, animal, or object. This changes the depth of your investment in the outcome.

You get to make decisions. You, and perhaps also the others that are playing, dictate the outcome of the experience.

This provides an opportunity to learn, get better, and improve your decision-making and skills. The feedback might be instantaneous or over time. It may come from the game or other players.

You may be playing with other players collaboratively or competitively. But even if you are playing alone, games build communities around shared interests within the game or even outside of it. They can form a connection between people with nothing else in common.

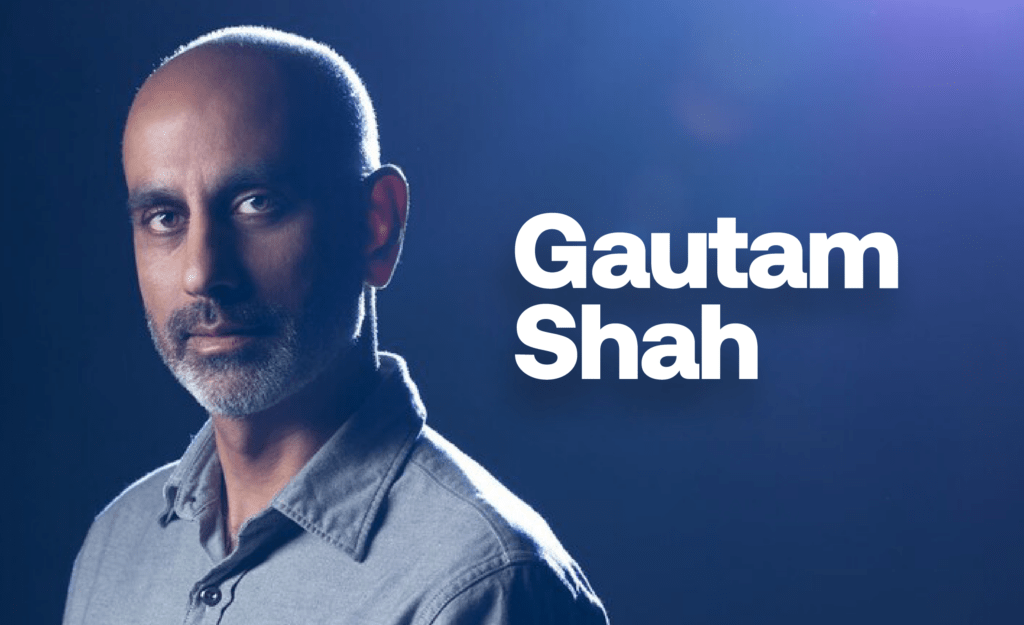

We’ve been making wildlife documentaries for 70 years. There is an infrastructure for funding them and a formula for making them. We know exactly what we’ll get at the end of it. Whereas games are still scary. We don’t know the business models or how to reach people. The risks seem too great. They might have a higher ceiling but also a lower floor.

While dozens of different game genres and thousands of games have seen success, the ones that get the most attention tend to be more violent or dystopic in nature, lending to the argument that games promote unwanted behavior in youth.

A triple-A game will cost as much or more than your most sophisticated episode of Planet Earth, and at the other end of the spectrum, it is easier to put together a small film crew and do a shoot than design, build, and release a low-budget game.